Waste converted to Clean Water

The

sewerage system is now an important component of the water cycle, with

water-borne human waste being collected, treated and returned, as cleaner

water, to the water cycle, into rivers or the sea. The primary function of

sewage treatment is to break down faeces and remove harmful microbes from the

water. Sewage plants also have a role to play in removing harmful chemicals

from water. In heavily populated parts of the world, water passing through

sanitation systems represents a substantial proportion of the water flow in

rivers. The River Lea, which runs from Hertfordshire in England into the River

Thames, would probably cease to flow for much of the year were it not for the

output from sewage plants (Brown, 2002).

The

population in many of the world's megacities is growing so fast that the

development of effective sewage systems is not keeping pace. In cities such as

Karachi, in Pakistan, the water supply, mostly from groundwater, is heavily

polluted by untreated sewage and contains high levels of bacteria (Rahman et

al., 1997).

If predictions about a

shortage of water for half the human population in 2025 seem alarming but far

away, it is important to point out that, for many people, a water crisis is

already a daily experience: many people in the world already face the severe

adverse consequences for their health of having insufficient water and water

that is also polluted. This is particularly true in Africa.

Above image and text sourced from OpenLearn

under a Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Licence

http://openlearn.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=398708§ion=1

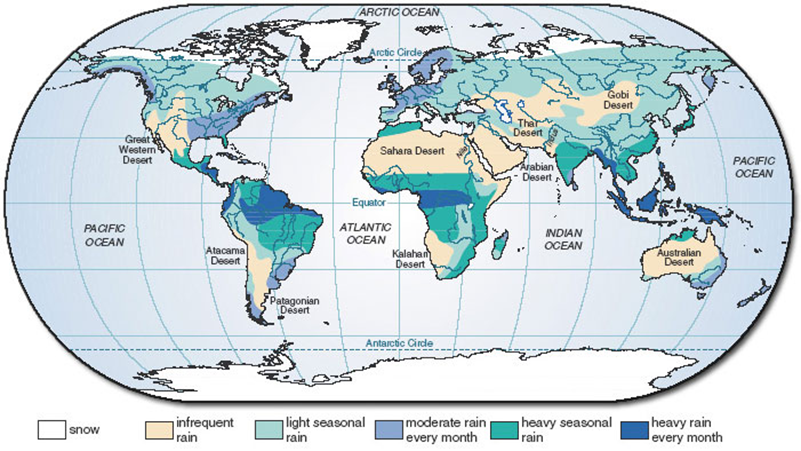

People in many parts of

the world currently face a chronic shortage of water. This is a developing

crisis that is expected to get worse. Several factors underlie this dire

prediction but in addition to these, climate change is expected to cause major

changes in the distribution of freshwater. The uneven distribution of

freshwater across the world is illustrated here

Above image and text sourced from OpenLearn

under a Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Licence

http://openlearn.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=398708§ion=1

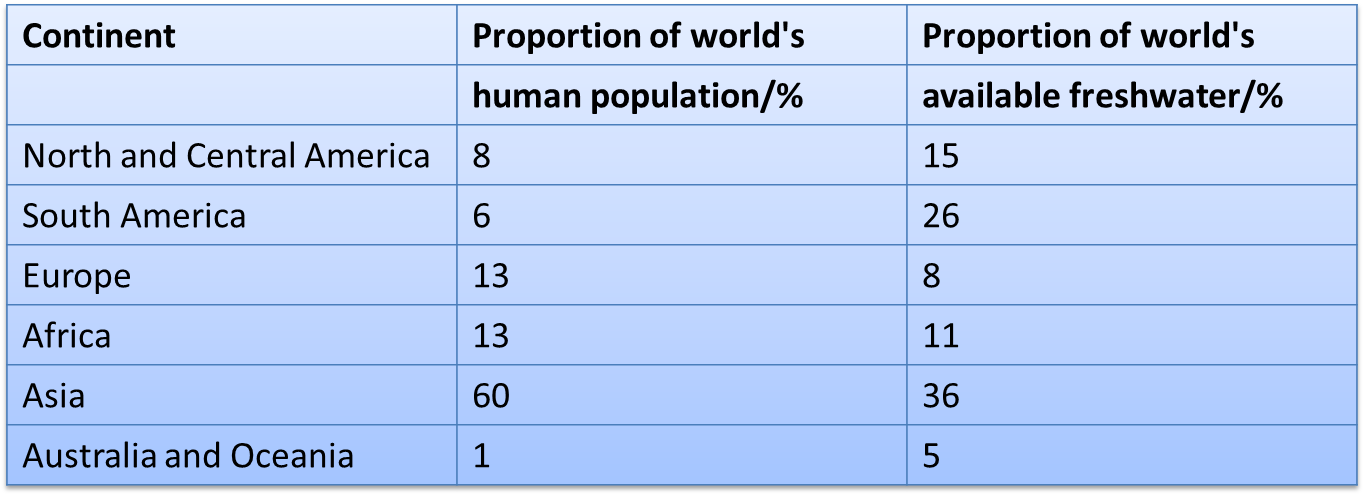

People use water for a

variety of purposes. As well as water for drinking, people use water to wash

in, for sanitation, to irrigate the land for crops, to give to livestock, as a

source of food (fishing), for transport and for recreation. The major

categories of water use, on a global scale, are (in order of increasing use)

reservoirs and municipal needs, industry and agriculture – the last being the

most demanding in terms of water use.

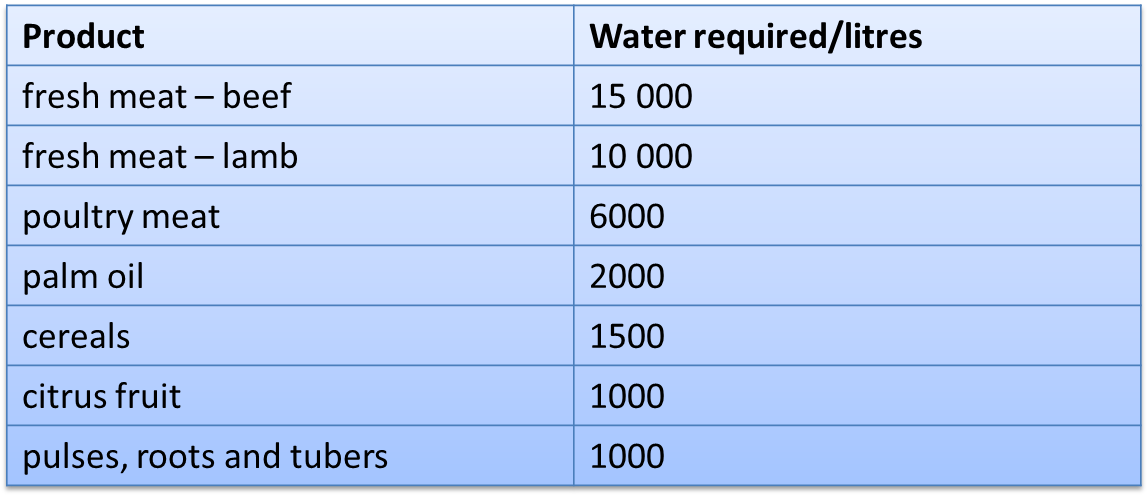

Water use in agriculture

is of two kinds: irrigation of crops and watering of livestock. Many methods of

crop irrigation are wasteful of water in that much of it is lost into the air

by evaporation before it is taken up by crops. Livestock use even more water.

Below the amounts of water required to produce various major food products are

compared. Notice how ‘expensive’ it is to produce beef and lamb in terms of

water requirements.

http://openlearn.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=398708§ion=1

Volume of water required to produce 1

kilogram (kg) of specific food products

(Source: data derived from UNESCO, 2003,

Figure 1, p. 17)

The

availability of freshwater will be significantly altered in a future world

affected by climate change. In some regions, water availability will decrease;

in others it will increase. Precise predictions about the extent and exact

location of such changes cannot be made because they are based on climate

models, the accuracy of which is uncertain. However, there is wide agreement

that probable changes will include:

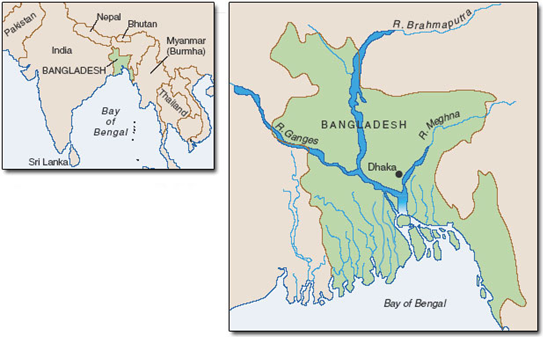

Rising

sea levels, which will lead to flooding of low-lying coastal regions, including

major flood plains and river deltas, many of which are currently densely

populated; for example, the Bengal delta in Bangladesh

contains 8.5 million people (Hecht, 2006

• More

rain in northern high latitudes in winter and in the monsoon regions of south East

Asia in summer.

• Less

rain in southern Europe, Central America, southern Africa and Australia in

summer.

• Greater

water flows in rivers that are fed by glaciers.

• Overall,

higher temperatures in all regions, which will lead to greater evaporation so

that, even in regions where rainfall does not decrease, water availability will

be reduced.

Desertification already

“affects more than 110 counties, threatening the survival of more than a

billion people (UNCCD 2009), and the population of the arid regions is

increasing even faster than the world average (Hillel 1994, 33).” Guttmann-Bond (2010, 359)

http://openlearn.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=398708§ion=3.2